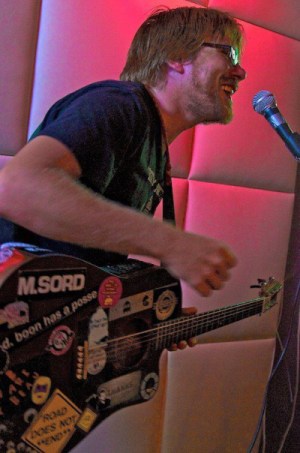

Hailing from Brooklyn, Brook Pridemore is a singer/songwriter that has been building a career for himself over the past decade. He plays a stylistically eclectic assortment of folk, punk, rock, and dance. Currently unsigned, Pridemore draws on influences from the likes of M. Ward, Neil Young, and several others. I sat down with Brook to talk about his music and life:

Ryan Kearns: What gave you the initial push to start your musical career?

Brook Pridemore: My grandma reminded me, a few years ago that, when I was a kid, I would sit in front of the TV, playing with toys, or whatever. I’d ignore the programs, but drop everything to sing along with the commercials. I don’t remember that, but I DO remember wanting to sing, as I got older. I wanted to be a singer, like Boyz II Men, or Nirvana. But, since I only really fit in with other nerds, and it would be years before it was considered cool to be a nerd, I thought I couldn’t be in a rock band. I thought Rock and Roll was something you were born into. In Winter, 1993, I heard my first They Might Be Giants record. They wore street clothes onstage, and the guitar player wore glasses. Best, their songs were about something besides sex and drugs. I didn’t know what their songs were about, but that was part of the intrigue.

That same Christmas, I got my first guitar, and my first Dead Milkmen CD. The Milkmen were an important discovery because they were nerds, like TMBG, but they were pissed. I started stumbling forward, into a life of creating music. I had never had a method of self-expression, before I discovered music. I am still socially awkward, offstage. But, through song, I have a way of getting ideas across to people.

Ryan: You are affiliated with the anti-folk scene. To be honest, I know nothing about it. Care to explain to what the scene is about and your experience taking part it in?

Ryan: You are affiliated with the anti-folk scene. To be honest, I know nothing about it. Care to explain to what the scene is about and your experience taking part it in?

Pridemore: The real answer to this question takes hours to deliver, is really boring, and is entirely up for debate. What follows is what “Antifolk” has come to mean to me, as a songwriter, over the past decade.

I came to New York in 2002, after I finished college. At my school, I was one of two guys on the folk scene who wrote original songs. Neither of us were any good, but there was me and another guy, and everybody else just did covers. I thought I was creating high art, and would turn my nose up, at the other guys. I knew about Antifolk, after hearing Jeff Lewis’ first album. I knew I had to find these people. When I arrived in New York, I thought the Antifolk scene would be my ticket to overnight stardom. Turns out, it’s been a whole lot more.

My first Monday night Anti-Hootenanny (held at the Sidewalk Cafe in the East Village, and understood to be ground zero for Antifolk), Kimya Dawson and Langhorne Slim were among the first five performers. I was listening to Ryan Adams’ “Heartbreaker” on endless repeat, trying to be a sensitive folk guy. These people were edgy, funny and smart. I realized pretty quickly that I had to either step up my songwriting game, or find a new method of expression.

Thankfully, Antifolk is nothing if not forgiving. Matt Roth said it best when he said that “Antifolk is about process, not product.” It’s essentially a community of like-minded people who get together to workshop the newest, freshest work in their catalog. Some are better than others. Some start sloppy, but grow. For a long time, I didn’t consider a new song to be “officially debuted” until I’d played it on Monday night. For me, Antifolk is where I cut my teeth, where I made my best friends and musical collaborators, and where I can still go to try out new stuff.

Sound-wise, don’t get me started. If you want to be Antifolk, start calling yourself that. No one is going to stop you. I consider it a self-diagnosed genre.

Ryan: Your first LP Metal and Wood dropped in 2003 and your latest LP Gory Details scheduled to drop this year would make it a decade between your debut LP and current day. How has your songwriting changed over the past ten years?

Pridemore: Well, Metal and Wood is a collection of earlier material, recorded before I moved to New York, and filled out with some solo acoustic stuff recorded in fall 2003. I had met Dan Treiber, then the head of Crafty Records, at a show I played with King Missile and Corn Mo in summer ’03. Dan wanted to do an album with me, but didn’t have the money to do new full-length. I suggested we release a compilation of earlier work.

Metal and Wood is important to have around because it reminds me how much I’ve learned about song structure over the past ten years. Several of the songs top the six minute mark, and it’s almost 80 minutes long, which is twice as long as the second longest album I’ve released (A Brighter Light). My favorite moment on it is the song “Teeth,” which I had finished writing in the car, on the way to the studio. I still can’t tell you exactly what it’s about, and I wrote it.

Since then, I’ve been moving toward this ideal of an album having a beginning, a middle and an end, wherein the narrator undergoes a crucial psychic change. Also, I’ve tried to make albums that rock progressively harder, that reflect my current influences without openly aping them, and to try new tunings and new instruments. By circumstance and necessity, my last three albums have all had a different rhythm section, too.

When I started writing Gory Details, I knew I wanted the songs to all be in relative keys to each other. So basically, if the first song was in D, the second song would be in G, and the third in C, and so on. I presented myself with a challenge, setting out to write a series of vignettes that related closely to one another, and flowed in a way that wouldn’t be immediately apparent to the average listener. My favorite aspect of Gory Details is that it begins and ends with a single strum of a D chord and, while each is deliberate and desperate, each manages to convey a different emotion.

Ryan: Speaking of Gory Details, how has the experience been bringing that album to life and what can people expect from the album?

Pridemore: Crafty Records folded. It was really time. All of the other bands on the label had either broken up or decided to take their music elsewhere. I told them I was going to do my next album without them. As it happens, Dan Treiber was an important part of the making of Gory Details, and we still work together on a vastly reduced basis.

I finished the songs in Winter 2011. I had been playing with this band, who were called Brook Pridemore’s Gory Details. We kicked ass. While I was on a European tour, though, the other members’ lives got too big to continue playing with me, and they moved on. I spent a while figuring out what to do with the new album. I very nearly made it a solo acoustic album. I very nearly sang the songs into a tape recorder, mailed one copy to the girl who’d inspired them, and walked away from it. I very nearly played all the instruments, myself. I talked to twenty drummers and fifteen bassists, all of whom were game, but seemed wrong for it. It finally occurred to me that I could just get the guys from the band to play in the studio, and worry about the live band, later. Doug “Bermuda” Johnson and John Telethon were readily available for a couple of sessions, and I recruited Pope James Gibson Telfer IV after I saw him playing upright bass, one night. Brian Speaker and I recorded the songs at SpeakerSonic Studios. Brian’s the best at what he does. We recorded very slowly, for what I’m used to. The whole process took about six months, we were very meticulous, and got everything right.

And then, a funny thing happened. We finished recording in February 2012. I hadn’t written a song in over a year (that’s a very, very long time, for me). I had no clue how to get the record in the hands of a new label, and I knew I didn’t want to self-release it. I thought I was done writing songs. I decided to send my last batch of songs off with a bang. I had had fun making music videos before, so I thought it would be fun to try and make a video for every song on the album. We’ve shot eight of them so far and, wouldn’t you know it, somewhere in there, I started writing songs, again. I was able to start a new band, with Telfer on bass and Daniel Muhlenberg on drums. We’re heavier and tighter than any band I’ve played with, before.

If and when my manager and I finally find a home for Gory Details, I hope listeners find it as funny, heartbreaking, smart and dance-able as I do. I really am incredibly proud of this work.

Ryan: There has been a legislation recently introduced in Congress called the Internet Radio Fairness Act. This legislation will allow Internet radio services such as Spotify and Pandora to pay reduced royalties to artists and record labels. The main way most people enjoy music is through these services and bands get a fairly low royalty rate as it is. How do you feel about this situation? In addition, how do you feel about these services revamping the music industry?

Pridemore: I have never been paid a dime for my music. Literally every cent I have made off my records and touring has gone into the vault to pay for the next record and the next tour. That said, no one else is making money off my music, either. In that Rodriguez documentary, his daughter says, “He is not a rich man in terms of money,” and it has only recently dawned on me that that is becoming my truth, as well. No amount of money can buy the world I’ve gotten the chance to see. However, were this music to become a money-making commodity, my palm had better be the first one to get greased.

Ryan: I must say that I enjoyed the video for your song Celestial Heaven. How was the video developed and is there any underlying messages that the viewers should pick up from watching it?

Pridemore: Casey Mathewson and I bonded over our shared love for edgy comics and huge portions of mutton. He was a photographer, and wanted to break into film. I suggested a music video, and he came up with the basic message that, from waking up to showtime, Brook Pridemore plays music through it all. He wanted to include footage of me eating a taco, because he thought I looked funny while eating.

The song is about a dark period in my life, where I knew I had to find a God to believe in; specifically, a weird couple of months wherein I attended a Spiritualist church, prayed to leprechauns and researched the Mormon church. The conclusion I was led to was: You have to believe in something. Whatever you choose is fine, because it’s all the same thing, anyway.

Ryan: Where do you find your source of inspiration for songwriting?

Pridemore: Life. My friends. Walking around. The most consistent way I make up a melody is walking around, humming something in my head. If I can keep it, I’ll try to flesh it out into something. I’m also in tune with what I’m listening to, and use that influence to craft my songs. I knew I wanted Gory Details to be punk like The Promise Ring and folk like Neil Young, so I listened to a lot of both artists. “Celestial Heaven” is an obvious example of that, what with the “Doot doot” part, at the end. I wear my influences on my sleeve, because we all have them, and my enthusiasm about some weird old record might spurn someone else’s curiosity about something they haven’t heard.

Ryan: One of my personal favorite songs of yours is “The Reflecting Skin”. How did the song come to life?

Pridemore:“The Reflecting Skin” is a 1991 movie, directed by . I’d seen it once, in college, and had been deeply moved by some of the movie’s more graphic scenes. It’s a pretty bleak film, about post-war life in a small Great Plains town. Some of the lines in my song were lifted directly from the movie.

While I was writing this batch of songs, I started outliving friends of mine. Between Spring 2004 and Fall 2005, three friends of mine passed away by their own hands. I had fallen out of touch with all of them and wished I could have helped. As the months passed, though, I realized that every man is responsible for his own actions, and I was powerless to save any of those men. I vowed then and there to live my life to the fullest. The line about the bathroom is intended to give the listener an idea of the dive bars I was playing in (and still do play), and the line about being good without a fight is my battle cry: that I will not go gently into that dark night.

Ryan: One of my favorite musicians, Brandon Boyd, believes that art and music are a great means of driving social change. Do you follow the same mindset or do you differ?

Pridemore: Well, yes. Art can effect social change. My music can, in the right (or wrong, I guess) have a profound impact on social change. But I don’t spend a lot of onstage time talking politics, because I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about politics. As a performer, I’m more concerned with making people’s lives a little brighter with my songs, than anything else. I hope no one gets hung up on what opinions I may express offstage, or on how my lyrics can be interpreted. My opinions change, and while my lyrics don’t, they do come to mean different things, with time.

Kurt Vonnegut once said something like, “The job of every artist is to make people forget about how awful life is, even if only for a little bit.” I consider myself charged with that task. How people interpret my songs is none of my business.

Ryan: When I listen to your music, the one thing really drew me to appreciate it is that it reminded me of John Darnielle’s work. How big of an influence is he on your career if at all?

Pridemore: Yeah, I’m a big Mountain Goats fan. The only thing I’ll say in my defense- if someone suggests I’m a little too derivative-is that I sounded like this before I heard them. But yes, I buy every record the day it’s released (I want there to always be record stores), and I’ve seen them live, like ten times. John has three of my records, and I hope he likes them.

Brook Pridemore’s Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/brookpridemoremusic

Thanks for the article. I really did not know the proper term for this beautiful new music. I really like it.